I got thinking about the Book of Job after La Coulter made fun of Howard Dean for choosing Job as his favorite “New Testament reading.” Dean is an unsharpened pencil, for sure, but he is right about Job. It’s unrivaled—easily the best book in the Bible.

In case you wondered why an irreligious, if fierce, defender of the Judeo-Christian tradition is expounding on the Bible, let me explain. I’m of a generation of Hebrews that knows and loves the Hebrew Bible for the tremendous literary, philosophical, and historical achievement it is. Those who’ve studied them in Hebrew as I have know the 39 Books for the vital, earthy, pioneering, and fascinating works they are.

In “A History of the Jews,” Paul Johnson writes: “The Bible is essentially a historical work from start to finish. The Jews developed the power to write terse and dramatic historical narrative half a millennium before the Greeks.” A quick glance through the clunking Qur’an and one appreciates even more the power of the biblical narrator.

The Jews also developed an ethical monotheism centuries before classical Greek philosophy. Deuteronomy—the fifth book—showcases an advanced concept of Jewish social justice, and is replete with instructions to succor the needy, and protect the poor, the weak, and the defenseless. The prophets inherited the mantle—they railed magnificently against injustice and corruption.

Although contemporary Jewish leaders have labored to cast Jews as a mere faction among the multicultural multitudes, the proper metaphor for the relationship between Judaism and Christianity is that of parent and progeny. In speaking truth to power, Jesus followed in the footsteps of the classical prophets.

But back to Job. Considering the period, the book is a radical philosophical masterpiece. As follows:

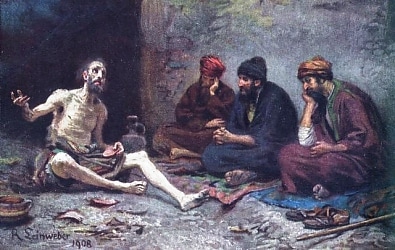

Job was a man of probity, piety and great prosperity (in Jewish tradition, wealth is a blessing). Nevertheless, God puts him through a succession of horrible trials. Job’s fortune is lost, his kids killed, and his body ravaged by a skin condition that renders him a writhing wretch.

Yet despite the troubles God inflicts upon him, Job refuses to renounce or denounce the Almighty. He is raked over by the assorted “Job’s comforters.” They tell him he must have sinned or else God would not have struck him. Job rejects this proposition as false, refusing to confess to sins he did not commit. Simultaneously, Job is persistent in his love for the Lord: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return there. The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; Blessed be the name of the Lord,” says he.

Job’s actions are those of a rational individual—a man of conviction who believes in the immutability of reality and truth. Best of all, by steadfastly maintaining that he is right, Job is, by extension, saying very plainly that God is wrong. On the evidence, Job is right. He is patently innocent—an upright man of God, unjustly punished. What’s more, God eventually sides with Job, admitting He was only testing the depth and degree of Job’s faith.

How radical is that? A mere mortal stands his ground with God, who then agrees with him. Such principled defiance in the Qur’an would have ended with a beheading—Job’s stiff neck would have been “smitten.”

Biblical literalists will jump out of their skins at my suggestion that God was wrong and that the Book of Job all but concedes the point—implicitly, at least. To that, let me say this: The Almighty never disputes that Job was right in proclaiming his innocence. By logical extension (deduction is integral in Jewish thinking), this implies God was wrong to punish Job. By restoring Job and admitting he was without blemish, God acknowledges by default that He acted unjustly toward Job.

The book of Job is still the quintessential theodicy, precisely because it entertains and reconciles the possibility of a fallible God. Then again, Jews have a tradition of arguing with God. Jacob wrestled physically with the angel of God. And Abraham haggled for the sinners of Sodom and Gomorrah because he disapproved of the verdict God pronounced upon them. Job, in a manner, also argued with God and prevailed, a very unorthodox concept, considering the times.

Now, Job challenged the ultimate authority, not because he was rebellious, but because he was righteous and true to himself.

Contemporary parallels to Job’s individualism are hard to come by, not least because the State has replaced God as the ultimate authority. Other than principled libertarians, nobody challenges the god of government in any meaningful way. Our Delphic oracles are the pundits and assorted self-styled presstitutes. Their Delphi is the TV on which they primp, preen and parrot party falsehoods. They can strike a pose but they can’t oppose.

Addendum: I realize my valued Christian readers will take issue with my discounting the centrality of Satan in the column. However, my analysis is typically Jewish, the emphasis being on the individual’s relationships on earth and to God. (This take, furthermore, coheres to my father’s analysis—he is a rabbi and a Talmudic scholar.) In Jewish tradition, Satan is far less prominent. God’s the boss, after all (besides which man has free will and can resist evil).

©2006 By Ilana Mercer

WorldNetDaily.com

October 27

CATEGORIES: Ancient History, Christianity, Individualism Vs. Collectivism, Jews & Judaism

print

print