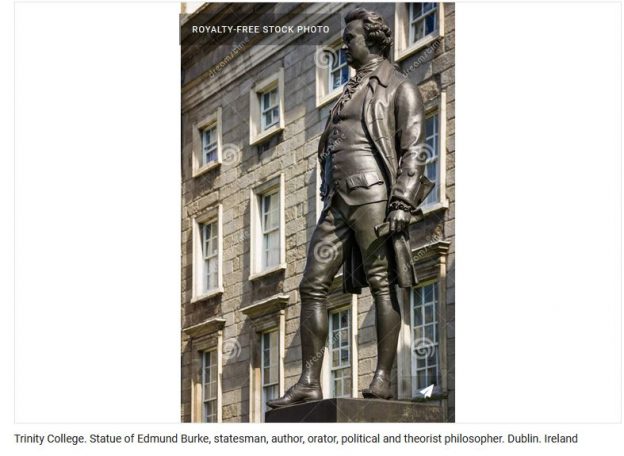

What follows is the first of a two-part conversation with Dennis O’Keeffe, Professor of Sociology at the University of Buckingham, and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of Economic Affairs, “the UK’s original free-market think-tank, founded in 1955.” We discuss the subject of Professor O’Keeffe’s latest book, “Edmund Burke.” (Part II is “The Moronizing Of Modern Culture.”)

Ilana Mercer: Other than that he was a “great publicist of the American Revolution,” what are the most important things Americans ought to know about Edmund Burke, whom you consider “the greatest Irishman who ever lived”? (P. 124)

Professor O’Keeffe: Burke greatly admired the American colonists, citing especially their economic success. He believed America reflected the same principles of freedom and order which had emerged in England. He said the British had lost their American colonies through their own bullying policies. Ever the realist, Burke insisted that they must accept the loss as irreversible. Burke failed at the time, however, to understand that a new nation had appeared. Had he known about modern American history, he would have been as grateful to America as most British and Irish people are today. Just as Burke pioneered the understanding of freedom and political decency, in relation to the American question, for example, so he penned the most astounding, pioneering sociology of despotism in history, his “Reflections on the Revolution in France.” Burke’s sense of politics surpasses in its acuity Machiavelli’s. It at least rivals that of Aristotle, an amazing achievement for a man whose thought was all policy-focused.

Ilana Mercer: Why is it that one rarely hears Burke mentioned in American public discourse, yet my countrymen know and love Thomas Paine, who sympathized with the Jacobins and spat venom at Burke for his devastating critique of the blood-drenched, illiberal, irreligious “Revolution in France”?

Professor O’Keeffe: Even Thomas Jefferson seems not to have grasped at first how different the French and American Revolutions were. The confusion continues today. Paine belongs to the Che Guevara ascendancy, which admires nothing unless a good dose of murder is present. There are American scholars, however, like Peter Stanlis, and Francis Canavan, who appreciate the utter consistency of Burke’s outlook with the main tendencies of American civilization. Burke said the French Revolution was murderous and would have terrible consequences. He was borne out, not only by the bloody course of the Revolution itself, but by the Communist and Nazi menaces, which drew their inspiration from and surpassed in their wickedness, the pathology of Revolutionary France. The USA played a huge part in defeating these modern despotisms, and modern France very little.

Ilana Mercer: A mutual friend, political philosopher Paul E. Gottfried, assures me that “there is a bad fit between Burke and American political reality. America was founded as an eighteenth-century liberal republic,” says Paul, “and not as a reconstruction of the kind of British aristocratic-monarchical society that Burke defended in his ‘Reflections.'” This is not what I took away from your penetrating study of Burke. Who is right about Burke’s centrality to American (and any other) ordered liberty?

Professor O’Keeffe: British people even now mostly feel very at home in America, as a successful version of their own way of life. Professor Gottfried is right that liberal republicanism differs from conservative monarchy. He omits the consideration, however, that, like Burke himself, British monarchy and aristocracy were also liberal, and that the liberal/conservative synthesis was exportable. Being in America, or Australia, or Ireland today, is very like being in England. We can today regard the synthesis as the principal British imperial export. Burke was wedded neither to monarchy nor aristocracy, nor was he hostile to republicanism as a form of civilized order. Unsurprisingly, the American intellectual elite has always resembled the British one. Burke upheld individual freedom and collective order. He thought that the meanest soul in any decent society must be protected against injustice, a condition England subsequently achieved, domestically, earlier than America, because the British kept their slaves in the Caribbean. Burke knew well that many empires have been vile. He would have regarded modern America as a civilized (classical) liberal/conservative empire.

Ilana Mercer: Based on your book, I would go further in challenging the popular conception about the marginal role Burke has in American conservatism, and say that the American abhorrence of aristocracy is wrong-headed. As you brilliantly illustrate, Burke was not wedded to the inherited “mode of governance,” but, rather, to he principles of “mutual consent and a strong sense of duty” in leaders (p. 26). He believed in an aristocracy that was “open to recruitment of talented persons from below.” Is this not the “natural aristocracy among men” which Thomas Jefferson considered “the most precious gift of nature”? In an 1813 letter to John Adams, Jefferson described this natural aristocracy as distinguished by “virtue and talents,” and disavowed “an artificial aristocracy… without either virtue or talents.” Please comment with reference to the ascendancy of the American Tea Party vs. the decline of the establishment thugocracy.”

Professor O’Keeffe: You are right that Burke admired British aristocracy, not for its ascribed character, but because of its decency and openness. You are right that mutual consent and pursuit of duty are crucial to leadership in free societies. Furthermore, unequal distribution of talent does entail meritocracy, a spontaneous “aristocracy” among men, such as Jefferson favored. If Americans applaud “natural hierarchy,” however, why do they denounce the hereditary version? In the British case this was simply an organic growth, not transferable elsewhere. The American Tea Party today is a reaction not against natural leadership but against arthritic, hypertrophied government, which fails to make best use of talent, and an entrenched government apparatus which recruits hacks to reproduce its interests. This political pathology is worse in Europe than in America. Modern American government deserves censure for its relentless expansion, debt compilation and on-going flirtation with socialist medicine. It has, however, committed no offense against the American people as gross as the handing over, by the British political class, of British wealth and power, to the blatant socialist politicos of the European Union. America still maintains the Burkean insistence that civilization is a contract between the dead, the living and the unborn, a contract which the British have now relinquished.

©2010 By ILANA MERCER

WorldNetDaily.com

October 22

CATEGORIES: America, Britain, Classical liberalism, Conservatism, Founding Fathers, Government, INTERVIEWS, Political Philosophy

print

print