Confronting Tolkien’s mediocre, myth-obsessed mind, Hugo Dyson, a member of Tolkien’s inner circle, let rip with a spontaneous slip of the tongue. Dyson “once reacted to a Tolkien reading with, ‘Oh no! Not another f—ing elf!'”

My response was a little more muted. “Lord of the Rings,” I had written, “appeals to adults with a proclivity for hobgoblins and gobbledygook.”

Recent ferment makes the nation’s entertainment choices even more alarming than I had previously thought.

In fact, it is particularly significant that a country which has created its own fable of reality in Iraq manifests a disturbing preference for entertainment with mythical and infantile subject matter. The American solipsistic view of reality lends itself nicely to the preoccupation with Tolkien, Harry Potter and, now, Peter Pan.

Having said this, let me offer a correction: Tolkien appeals to adults who believe in hobgoblins – the kind who believe that hobgoblins can make WMD vanish and can also unleash democracy from a genie bottle.

While I don’t often visit the surreal cinema, I do make an exception for films about the South. The reason is simply this: The road to national sanity leads through the South. The republic, RIP, can only be revived once the central government – which voided the Constitution to invade the South and, by legal extension, the rest of the once-sovereign states – is driven back. If Hollywood – hugely influential in shaping American lore – begins to get its ducks in a row about Dixie, then there’s some hope.

The latest epic about the South, sadly, leaves little confidence in such an epiphany.

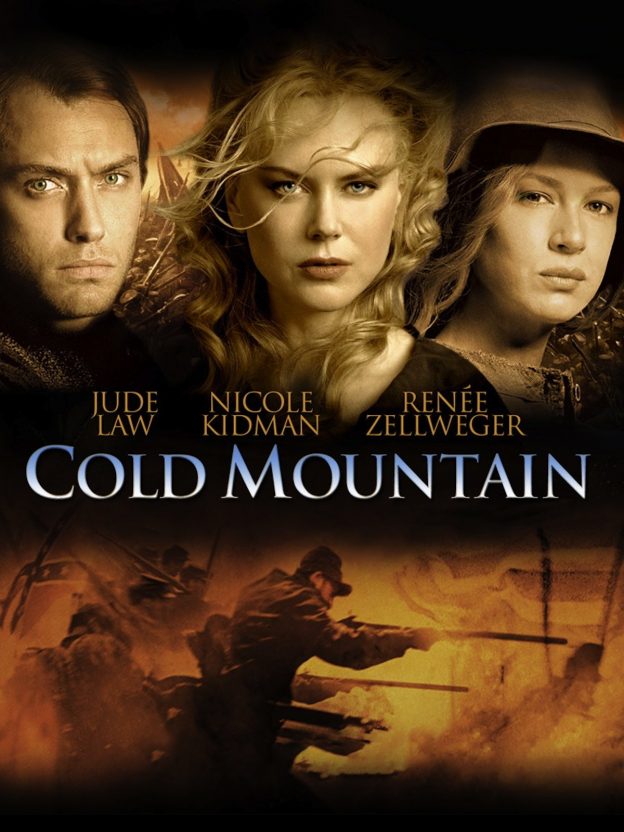

Director Anthony Minghella once turned a soporific, indecipherable book called “The English Patient” into a rather good film. With “Cold Mountain,” Minghella manages no such miracle. Most likely because the book on which the script is based was dead on arrival, which is also how most of the characters in the film end up.

This, of course, is not an unreasonable scenario considering that Lincoln launched a war of aggression that killed 620,000 people, including civilians, and devastated the Southern economy. This plain fact is missing from the movie, but like all Hollywood fare, films about the South are seldom burdened by fact. Thus the battle to vanquish the invader had little to do with slavery – most of the men fighting for the South had never owned a slave. The same is true for those they left behind. The fight was for freedom from the Federal Frankenstein.

The book’s insipid author, Charles Frazier, boasts some sort of ancestral connection to the main protagonists. He, however, porcellanizes the Southern identity of the lovers by painting them as ideological pacifists.

So it is that Confederate soldier Inman (played by Jude Law) is asked by his lady love, Southern Belle Ada Monroe (Nicole Kidman – better an Australian actress than a Yankee), if “he had ever seen the great celebrated warriors.” Inman replies that he “wished to live a life where little interest could be found in one gang of despots launching attacks upon another.” While the standard contemporary plumb line – South evil, North good – is averted, a Southern hero remains neutral about one of the few just wars Americans have fought.

Aside being depicted as coarse (incessant potty talk), the portrayal of the apparently hooligan-like home guards plays to the stereotype of the murderous Southerner – most Southerners killed in the film are killed by their own.

Clyde Wilson, professor of history at the University of South Carolina, addresses “this fundamental dishonesty.” The home guards in the mountains of western North Carolina during the war, Wilson told me, were indeed also charged with corralling deserters. But these men, consisting of youth under the age of 16, men over 55, and the physically disabled, did not go around terrorizing and killing people.

In fact, their leaders were personally picked by Gov. Vance, who was a native of the mountains and knew the people well. Consequently, he selected the most respected old men in the communities. While they were definitely serious about finding deserters and persuading them to go back, the point was to return men to the army, not kill them.

Attempting to murder a black woman whom you’ve impregnated was evidently yet another Southern pastime. One of two men-of-faith in the film is caught red-handed preparing such an execution. Commentator Steve Sailor corrects this slander: “Contrary to popular ideas about steamy nights of miscegenation on the old plantation, African-Americans in the rural South are the least admixed with whites.” Strom Thurmond, says Sailor, was unusual, not least in love and longevity.

After being wounded in the Battle of the Crater, Inman has had enough of fighting and goes AWOL. His journey homeward takes him through a series of trials likened by some reviewers to Homer’s “Odyssey.” What propels him onward is Ada.

Back at the ranch, Ada, the iconic Southern woman, is being dismantled bit by symbolic bit. In Margaret Mitchell’s truly great epic, “Gone with the Wind,” the patrician Ashley Wilkes speaks longingly about the grace and gentility of Southern civilization. Our film, however, offers a subtle, postmodern deconstruction of the Old South, the natural aristocracy – the gentry and its values.

The historically superimposed Girl Power message of “Cold Mountain” trashes the “corseted” Southern woman. Here we do not find the steel magnolia that blossomed in the combined characters of Scarlett O’Hara and Melanie Wilkes. Instead, the kind of female the well-bred Africans of “Gone with the Wind” called “white trash” takes over, both figuratively and in the flesh.

The intrepid Ruby Thewes (courtesy of the very able Renee Zellweger) arrives to “teach Ada how to run a farm.” In no time, she habituates Ada to talk about “wrapping those legs around this Inman fellow.”

There’s a magnificent scene in “Gone with the Wind” where the now-indigent Scarlett O’Hara finds out that the New Class has imposed enormous taxes on her Tara plantation. Wilkenson, a one-time Tara overseer turned Yankee sympathizer, arrives with his long-time mistress (now wife) to survey the loot. As the gaudy gal begins to climb Tara’s stairs, Scarlett shouts, “Stop!” and then, “Get off those steps, you trashy wench … Get off this place, you dirty Yankee!” Tossing a fist full of Tara’s red earth at the couple, Scarlett promises: “That’s all of Tara you’ll ever get.”

Well, the postmodern author of “Cold Mountain” has had time to reflect, and he chooses to fix this historical class “injustice.” Ada invites Ruby to take over the farm, even giving her a legal stake in the property. Ruby transforms the “useless” Ada and prepares her for a world that is to be inherited by Yankees, carpetbaggers and others of the underclass.

At the film’s end, the Old Order has been inverted. The air is now thick with the smell of the herd: The mistress, sharing and shacking up with her new friends, has turned into commune member.

If “Cold Mountain” offers a measure of the popular mindset about the South and, by extension, about freedom and individualism, then things continue to look grim for our culture. Mired in myth, the American mind will, for some time to come, remain enthralled by The Federal Goblins – their guns, their hidden germs … and their agenda.

©By ILANA MERCER

WorldNetDaily.com

January 2, 2004

CATEGORIES: Abraham Lincoln, Film, History, Hollywood, Secession, States' Rights, The South

print

print