Mention Justice Department Überbloodhound Patrick Fitzgerald, and the Securities and Exchange Commission in one breath, and even the dimmest libertarian ought to see warning lights flash. These entities are involved in the recent indictment of Conrad Black, former chairman of “one of the world’s most renowned newspaper groups,” on “eight counts of mail and wire fraud.”

The SEC operates on an unconstitutional ex post facto basis; its victims have no way of foreseeing or controlling how vague law will be bent and charges changed in the course of seeking the desired prosecutorial outcome.

Propelling the SEC are politically voracious prosecutors. Aided by George Bush’s latest legislative abomination—the Sarbanes-Oxley Act—they can pursue any business executive as long as a lay jury can be convinced the unfortunate chap intended to mislead or stiff shareholders. This is as easy as pie, given the common man’s affinity for wealth creators. As America’s regulators run out of entrepreneurs to eliminate, so they seek fodder from among foreign investors, hence Black.

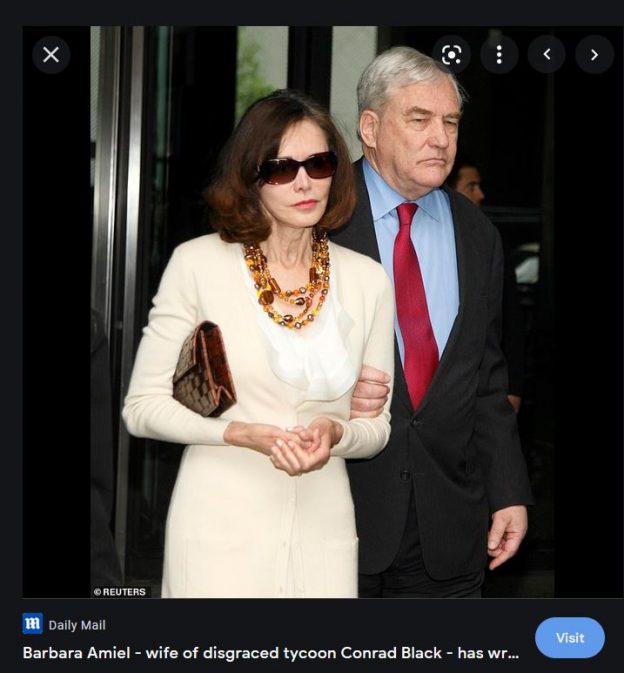

To mark the season of goodwill, and their commitment to liberty, however, a number of repulsive characters—including quite a few libertarians—slithered from dank epistolary corners, to cheer the state-orchestrated downfall of the former press baron, and wife, Barbara Amiel. Lord Black’s Hollinger International had owned broadsheets in England, Australia, America, Israel, and Canada, where I spent a few happy years kicking up a storm on two newspapers.

Under Black’s beneficent tenure, I scabbed at the Calgary Herald, during the Great Strike. There, absent editorial strictures, I wrote against coercive labor cartels, central banking, socialized medicine, taxes, the WTO, the apocalyptic Naomi Klein, and pop-philosopher Mark Kingwell.

Familiarity with the SEC’s naturally illicit laws and corrupt overseers, however, requires attributes journalists don’t usually possess. Thus the lazy and the unscrupulous elected to gossip rather than grapple with the issues. The orgiastic essays gleefully penned and posted by a certain coven of fringe libertarians, for example, were undergirded by this rickety reasoning:

Proposition No. 1: We hate all war-mongering neoconservatives.

Proposition No. 2: Black is one.

Ergo, Black (and bride) must fry.

Thankfully, there were exceptions. Economist Pierre Lemieux has been one of the few libertarians to speak up in defense of Black—and freedom. “Mail and wire fraud are just manufactured crimes by the Surveillance State—crimes that do not exist in civilized countries,” he told me. Lemieux has written that

“[W]e have no reason to believe fraud is involved, except if ‘fraud’ is defined in its politically correct, anti-business, catchall sense of today. In fact, ‘fraud’ has come to mean ‘what the state does not like.'”

I say state-coordinated witch-hunt, for if not for the energetic efforts of Tweedy Browne—minority shareholders in the company, who are also suspected by some of plotting a hostile takeover—a contractual disagreement would not have escalated to the point where “the founder and controlling shareholder” of a magnificent enterprise may face a 40-year jail term in the U.S. “The involvement of ‘the authorities’ in the case has been actively requested by rent-seekers—private parties trying to capture the state to serve their own interests,” inveighs the indomitable Lemieux.

The rotating directors have since proceeded to shake down the company like there was no tomorrow. So far Hollinger International has spent $100 million in pursuing Black over a contested $84 million. In Mark Steyn’s assessment, this is enough “to throw Amiel an indictable party every night for seven years.” Recall, one of the items in the U.S. v. Black alleges Black inappropriately expensed a birthday bash for Barbara. The new “stakeholders” also protested Amiel’s salary. Here’s Mark’s math:

“[F]or attending a few meetings these fellows earned in five months [$600,000 each plus a $600,000 termination bonus] what Tweedy Browne complained Miss Amiel had earned in five years. A second slate of squeaky-clean post-Conrad directors has now gone to court in Ontario to get the first slate of squeaky-clean post-Conrad directors’ bonuses reversed, running up more legal bills.”

For those able to get passed Amiel’s fondness for pricey pumps (“Manolo Blah-blah-blahnik”) and Black’s British peerage—the topics that have dominated the many hit pieces about the two—the quarrel is essentially contractual, involving salaries and perks. Abuses of expense accounts are alleged. Not all the expenses were properly authorized by the audit committee (the latter being a tyrannical new touch, courtesy of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which further federalizes corporate law). But then they were approved by the board, which later regretted approving them. Or is it the other way round? In short, a lot of kvetching about nothing. And certainly a matter for mediation, not the criminal courts, where a man’s life becomes fo

rfeit.

It’s worth adding that Tweedy Browne—which appears to have launched the investigation, and galvanized the law and grand-mal-inclined media—had no reason to grouse about unrealized gains. They did fabulously. According to a public filing dated July 8, 2003, their shares were worth over 50 percent more than they had paid for them.

The only serious charge on the rap sheet alleges that when Hollinger sold more than 100 Canadian newspapers to (the late and liberal) Izzy Asper of CanWest Global Communications, non-compete agreements were signed, and the proceeds pocketed by Black and associates, rather than by the company.

Perfectly libertarian, non-competes are restraints on trade, undertaken voluntarily. Steyn, once again, makes the case magnificently for Lord Black’s buccaneering capitalism:

“Young Asper made the reasonable point that, when you buy the Calgary Herald and the Edmonton Journal from Hollinger, you pay non-compete fees to Conrad Black in his personal capacity because he’s the one you don’t want coming back to town and starting up a rival paper. As Mr. Asper wrote, ‘If Lord Black ever decided to sell his interest in Hollinger, it is he —and not Hollinger—with whom we did not wish to compete.'”

The new guard has helped hollow Hollinger out, stripping it of a crucial asset (its founder), and thus causing a precipitous decline in share price. Soon there’ll be nothing but a husk in place of what Black built. Who on earth is going to shell out non-compete fees to these schlemiels?

This epic fight, more fundamentally, is about property; it goes to a proprietor’s prerogatives in the increasingly socialized corporation. As central to this disagreement—and to capitalism—is an acceptance of the risks associated with voluntary, consensual agreements. Writes Lemieux:

“Remember that he [Black] is the founder and controlling shareholder of Hollinger International. The other shareholders must have known that there was some risk that a large chunk of the cash flow would end up in Black’s pockets. Obviously, they thought that the risk was worth their expected return. Moreover, all Hollinger board members were sophisticated adults.”

But mostly, the bruising battle concerns an out-of-control, bloated behemoth of a state. Bush’s “New New Deal,” including the Sarbanes-Oxley’s sweeping provisions, has accomplished what FDR failed to: the final federalization of corporate governance law. This machine, now capable of occupying every company across the land, has been commandeered by private parties to do their bidding against Black. In the process, the rent-seekers and their racketeers have dismantled a business they don’t own.

True, Black presents us with contradictions. Relatively uncritical or unaware of America’s escalating autarchy, he shifted the lion’s share of his business from Canada, where the securities regulators are more benign, to the U.S., where the SEC, in the estimation of Cornell’s Jonathan R. Macey, threatens to stultify capital markets. Black argues against fascism, but, writes rather favorably about FDR, not realizing, as Lemieux notes, “that FDR was a founding father of our soft fascism”—and of the SEC.

But then Martha Stewart’s Democratic bona fides hardly prevented my protesting her unjust prosecution.

©2005 By Ilana Mercer

WorldNetDaily.com

December 2

CATEGORIES: Constitution, Criminal injustice, Economics, Economy, Law, Media

print

print